Tag Archives: Meryl Meisler

PWP Member Spotlight: Meryl Meisler at Westbeth Gallery

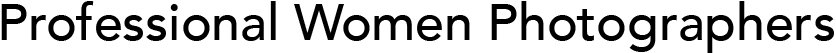

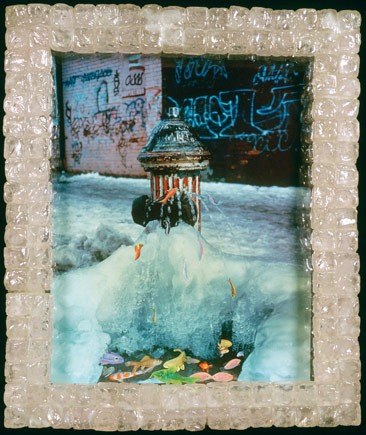

Professional Women Photographers’ member Meryl Meisler is featured in Omens of Climate Change at Manhattan’s Westbeth Gallery from February 1 – 16. Her exhibition space (two rooms!) is devoted to her Immersions series featuring New York City landmark buildings submerged under water and filled with aquatic creatures.

PWP: You are known for your tough pictures of Bushwick in the 1980′s. Why did you turn to a subject matter that embraces lightness and whimsey?

MM: In addition to being an art teacher in the New York City school system, I was also a freelance illustrator, and did a lot of work for educational publishers, including the New York Times Science Times, and Scholastic (Sea Otters: Little Clowns of The Sea).

When I was teaching in Bushwick, I started painting directly on my Cibachrome prints in a whimsical fashion. I also became a certified scuba diver, bought an underwater Nikonos camera and flash, and began photographing my underwater adventures in Florida, Mexico, the Bahamas, Honduras and Florida. I read Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea by Jules Verne and had visions of my beloved New York City submerged like Atlantis.

My work was published in Print Magazine and Zoom, and in 1991, I got a call from the art director of a new software company who selected me to come to the Maine Center for Creative Imaging to be among the first artists trained by Apple and Adobe to work on the Macintosh Computer with a new application: Adobe Photoshop. I was hooked, and began making digital images and mixed media sculptures based on aquatic themes.

PWP: What was involved in gaining access to the buildings?

MM: In 1995, I was selected by the MTA Arts for Transit to create an installation in twelve light boxes in Grand Central Station. My proposal to was “submerge” the terminal digitally, and I received permission to photograph there with a tripod and medium format camera. The resulting installation, Grand Splash, 1995-1996, was a huge success, the MTA’s first exhibit of digital work. It was featured in WIRED Magazine and Print Magazine, in addition to TimeOut and other periodicals.

I wanted to continue, and worked for three years to get permission to photograph the New York Public Library at 42nd Street and Fifth Avenue without paying licensing or rental costs (typically thousands of dollars).

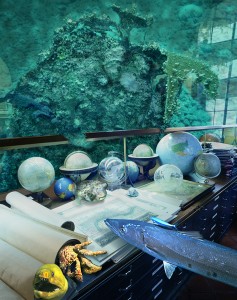

I was also commissioned by the MTA Arts for Transit to create Submerged, an edition of 4,000 posters installed throughout the NYC transit system from 2001-2002. It went up on the day of my 50th birthday–what a celebration! I started “turtle watching,” going to every station throughout the city to see my poster, which was also a self portrait. The Submersions series was awarded a NYFA Catalogue grant.

The Immersions series was the main focus of my work from 1991 on, but during a 2002 exhibit at the ISE Cultural Foundation, my world collapsed. My father passed away suddenly, and my mother who had Alzheimer’s, required full time nursing care. I was very close to my parents, and the mourning and loss was deep and profound. After that, Immersions no longer seemed relevant to my life.

PWP: What‘s coming up next?

MM: In June 2014, coinciding with Bushwick Open Studios, I have a solo show, A Tale of Two Cities: Disco Era Bushwick opening at the Bizarre Black Box Gallery. I frequented and documented the hottest NYC discos in the late 70’s early 80’s, but have never shown these pictures. Juxtaposed with Bushwick images from the early 80s and now, the installation will have the look and feel of a disco. The “Bridge and Tunnel” crowd barred from those velvet ropes and disco doors is now the hip crowd!

So many images, so little time!

Interview by Catherine Kirkpatrick

30 By 30: Meryl Meisler / Via Wynroth

30 Women Photographers on the Women Photographers Who Inspired Them

A Blog Series in Honor of Women’s History Month, March 1 – 31

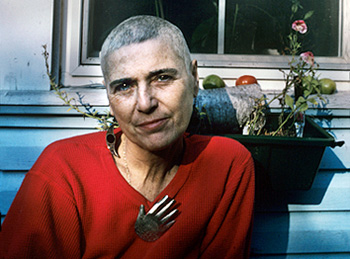

Meryl Meisler is a photographer and art teacher celebrated for her historic images of Bushwick, Brooklyn in the decades following the arson and looting of the 1977 NYC blackout. She has won fellowships from the New York Foundation for the Arts, Time Warner, Artists Space, CETA, the China Institute and the Japan Society. Her work has been exhibited at the Brooklyn Museum, the New Museum, the Dia Center NYC, MASS MoCA, and The Whitney.

Which woman photographer inspired you most?

MM: Via Wynroth, the first Education Director of the International Center of Photography-through her life, profession, and our personal connection as friends.

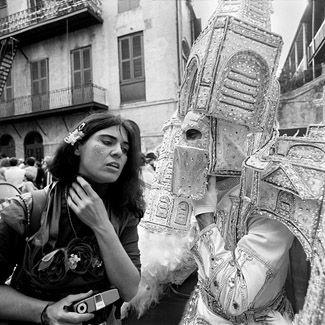

How did you meet?

MM: In 1977 we were both houseguests of Michael P. Smith and decided to enjoy Mardi Gras together. I had a Norita Graflex 2 ¼, and Via had a plastic Diana camera with color film. We went behind the scenes to visit the Mardi Gras Indians, the floats, the Jazz club Tipitina, then went on a big crawfish-eating frenzy. We returned to New York separately, but didn’t go our separate ways. We’d become dear friends.

What did she teach you?

MM: Via used all kinds of media and cameras-the Diana, 35mm, and 4×5-like a poet. She also made beautiful collages in shadow boxes with lace, velvet, miniature dolls, contact-sized photographs, even a deep violet butterfly! Recovering from a bone marrow transplant, she managed to videotape herself.

She taught me the importance of laughter in art and life, that equipment is less important than vision, that photography is mysterious, and teaching profound. Also that passion and integrity are more important than ambition and breaks, that time and health are never a given.

How did she come to photography?

MM: Via was born in Paris on February 20, 1940 to Jolan Gluck, and Oskar Gluck, a renowned film producer forced from his native Austria by the Nazis. It has always been my suspicion that in order to survive, that she was sent to live with a family in Paris. If so, she was another type of Holocaust survivor, a hidden Jew. After WWII, she was reunited with her parents in New York.

Via studied photography at the Art Institute of Chicago with Barbara Crane, then moved to Ithaca, New York, married, and became a staff photographer for a local newspaper. Her photos of the student protests and Students for a Democratic Society were published in Life Magazine.

But her parents were close friends of the Capas, and when Cornell Capa was planning the International Center of Photography, he invited Via to start an education program. She was the daughter Cornell and Edie never had.

Working in the education department at ICP in the 70s, did she feel a need to help women photographers?

MM: Via was empowered to imagine and bring to reality a model, radical education program. At a time when photographic education was mainly geared for commercial purposes, she founded a program that emphasized vision and art. She sought out and hired the radical, the inventive, the legendary and lesser known, men and women alike. It was a time when the idea of hiring men and women on their own artistic and intellectual merit was far from the norm. It wasn’t an “old boys club€ at ICP with Via in charge. I don’t know that she felt a need to help women photographers in particular, but she hired a lot of women photographers.

Why do women photographers matter?

MM: Whoa!! Why do women matter? Why does photography matter? This would take a lifetime of study, a PhD, a truth serum, a novel and many made for TV movies, plus museum shows and investigative reporting. They just do.

Via eventually took leave from her full time position ICP and traveled to Mexico. She would return to New York to teach ICP’s Summersite Programs, and on one of those visits, learned she had breast cancer.

She stayed, and found new joy in a home upstate in Cornwall, one with a marvelous studio. Via had lots of plans in the works: a one-woman exhibit and a book about her beloved Yucatan, that has yet to be published.

Mrs. Glück survived the passing of her only child, carried the sorrow, and maintained the house and Via’s studio exactly as it had been. When Mrs. Glück passed away, a friend cleaning the Cornwall house found Via’s photographic work that was going to be thrown away. Via’s friend Patt Blue put a halt to that and flew in from Texas to rescue Via’s work. Patt beseeched Steve Rooney, the CFO of ICP, and the ICP collections department took Via’s negatives and archives. Patt worked night and day for weeks to organize, box and bring in Via’s life’s work to ICP.

I will never forget Via Wynroth. When my spouse Pattie and I adopted a beautiful poodle/bichon with wavy black hair we tried very hard to come up with a name. Then Via, with her beautiful black hair came to mind and we named her Via, in honor of Via Wynroth. I’m sure they would both enjoy each other’s company and be proud to share their name.

[This blog post on Via Wynroth is part of a series about contemporary women photographers taking inspiration from other women photographers. The posts are usually about how the "inspiring" photographer's work touched them and affected their own work. In most cases, this inspiration is "remote," from a great, but not personally known photographer to another photographer. But in the case of Via Wynroth, it was not a "remote" mentorship, but an actual friendship. Other people who knew Via have gently corrected the details of her life that were mentioned in Meryl's reflection of her, and we have tried to incorporate these. It is wonderful to know that people care about Via and remember her, and we give thanks to them. She truly was inspiring.]

- Catherine Kirkpatrick, Archives Director

______________________________

30 By 30 blog series:

Intro: Dianora Niccolini / Women of Vision

Lauren Fleishman / Nan Goldin

Darleen Rubin / Louise Dahl-Wolfe

Dannielle Hayes / Diane Arbus

Meryl Meisler / Via Wynroth

Shana Schnur / Louise Dahl-Wolfe

Claudia Kunin / Imogen Cunningham

Gigi Stoll / Flo Fox

Robbie Kaye / Abi Hodes

Alice Sachs Zimet / Lisette Model

Juliana Sohn / Sally Mann

Susan May Tell / Lilo Raymond

Nora Kobrenik / Cindy Sherman

Caroline Coon / Ida Kar

Lisa Kahane / Jill Freedman

Karen Smul / Dorothea Lange

Claudia Sohrens / Martha Rosler

Laine Wyatt / Diane Arbus

Ruth Fremson / Strength From the Many

Greer Muldowney / Lee Miller

Rachel Barrett / Vera Lutter

Aline Smithson / Brigitte Lacombe

Ann George / Josephine Sacabo

Judi Bommarito / Mary Ellen Mark

Kay Kenny / Judy Dater

Editta Sherman / The Natural

Patt Blue / Ruth Orkin

Vicki Goldberg / Margaret Bourke-White

Beth Schiffer / Carrie Mae Weems

Anonymous / Her Mother

Fire, Ashes, Fear: Bushwick in the 1980s by Meryl Meisler

It just didn’t seem right. Why would a teacher leave a full-time post just before Christmas? Everyone knew Bushwick was dangerous. Was the teacher even alive? Had she been…killed?

Thus begins Meryl Meisler‘s artist statement, but in 1981 it was a real concern. She’d already had a camera stolen-not on the street, but in a classroom where she taught on the Lower East Side. But Bushwick, an area in north Brooklyn bordering on Bedford-Stuyvesant and Brownsville, was worse. Tourist guides left it out. No one wanted to go there. Meisler hesitated, but fearing she would slide down the Department of Ed. list, took the job.

In 1981 fear ran through the city. Dark days lay behind (the ’77 blackout, near bankruptcy, crime), and dark days lay ahead (more crime, AIDS, and crack cocaine). Every section was on edge, but some were worse than others. Bushwick was bad.

Its trip down had begun in the 1960s when working class families migrated to the suburbs, replaced by poorer families displaced by well-intentioned urban renewal projects elsewhere. As light industry and breweries vanished, so did jobs. There were Federal Housing Administration schemes, schemes by greedy landlords, and redlining by banks that stopped the flow of money to residents. Landlords torched buildings for insurance money and oust tenants, and kids torched buildings because there was nothing else to do. Fire was a deadly, ever-present threat. The number of Welfare recipients rose, and by 1977, 80% of the population was unemployed. Infant mortality rates were the highest in the city, schools were overcrowded, drugs were rampant and dropout rates were high.*

Many of the problems were citywide. From 1973 to 1976, New York lost 340,000 jobs,** and in 1975 came close to bankruptcy. 1976 saw the worst crime stats ever, as well as the debut of New York’s infamous serial killer, Son of Sam. How bad could it get?

Worse. On July 13th 1977, Meryl Meisler and a friend were planning to boogy down at Studio 54 to the throbbing disco beat of Donna Summer and KC & the Sunshine Band. But any sunshine New York had was fading fast and it was about to get very, very dark. At 8:37 p.m., lightening struck power lines at a substation in Westchester, triggering a short.*** As Con Ed managers struggled and failed to readjust electrical loads, lights winked out all over the metropolitan area. As Meisler and her friend pedaled uptown, the night seemed to grow increasingly thick. By the time they reached Studio 54, it was closed, and a great darkness-vast, enveloping and complete-had settled like a shroud over the City of New York.

Bushwick was the epicenter of chaotic looting that began and lasted into the next day. In the main shopping district along Broadway (named after Manhattan’s famous avenue), stores were cleaned out and many set on fire. When the anger and darkness and burning were through, Bushwick, an area that had clung to its working class identity, lay in ruins.

For New York, the blackout was rock bottom, the moment when all the terrible trends snowballed into one giant, awful photo op that the world, the country and the city itself could no longer deny or turn away from. Something-many things-had to be done.

When Meryl Meisler accepted the job in 1981, Bushwick had cooled down and settled into its role of urban ghost town. Photographic series exploring urban decay often feature great swaths of graffiti-covered brick, but in Bushwick, many of the walls that could have been written on simply weren’t there. Looking at Meisler’s pictures, the first thing that strikes you is the amount of rubble. It’s everywhere, all over the place-blocks and blocks of it-pierced only by an occasional tottering facade or low cluster of houses that seem to lean against each other for support. There is a sense of eerie quiet, almost peace; you feel the images were taken in some strange and distant ruined city, not a few miles from the financial center of the world.

Meisler took it all in with an unflinching eye. There were ruins that rivaled anything from ancient Rome, light unhampered by skyscrapers and very often the lack of any walls at all. The surviving structures “whispered stories” and seemed to be “waiting for their portraits.” She obliged. There were also street scenes reminiscent of small town life, and local characters who despite their poverty, conveyed a lively sense of joy.

Using a low-cost point-and-shoot camera with cheap slide film, Meisler began photographing on her way from the subway to the school, then back again on her way home. She was polite, always asking permission if people were present. When Adam Schwartz was planning a show on Bushwick in 2006, her name came up, and she began digging out the little boxes of slides, of which there are nearly two hundred.

They weren’t in great shape. There were color shifts, nicks, and green spots that surely were mold. She began digitizing, then used Photoshop to color correct and clean up flaws. Which, she believes, didn’t change the reality. Initially she outsourced the printing, but now handles it herself. “I am a printer’s daughter,” she says, “no one could be as obsessive about them as yours truly.€

Looking at the thirty-five images in the show, it’s easy to forget Meisler had a day job, but she did, and took it very seriously. She has won many awards, including a Disney American Teacher Award, an Adobe Youth Voices Grant, a Chase Active Learning Grant, and a New York Foundation For The Arts Fellowship. She also started a photography program at I.S. 291, integrating “the children’s personal stories, health topics and…the history of the neighborhood.€ Students’ work was exhibited in storefronts, parking lots, and projected onto building walls in addition to being shown alongside the work of famous artists in galleries and museums.

Till the blackout, Bushwick wasn’t on anyone’s radar. The focus always seemed to be someplace else, generally the Bronx, which drew the photo ops and attention of presidential hopefuls like Jimmy Carter. But after the blackout, with a mayoral election looming, Bushwick came to the fore. Prodded by extensive New York Daily News coverage, democratic frontrunners Ed Koch and Mario Cuomo pledged to rebuild the decimated housing stock. According to John Dereszewski, then District Manager of the Bushwick Community Board, it was a huge challenge: ”I remember walking through the area and tripping over the ground and wondering ‘what the hell am I doing here?’ Was it hopeless?€

The answer is no, but its rebirth has been a long, tough slog, that isn’t over. Redevelopment started, slowly, but the Koch administration began an immediate demolition program to clear abandoned buildings, which made making the area safer and less demoralizing. Trees were planted, and through community involvement and pressure, the housing that was built was in keeping with the low-rise nature of the neighborhood.**** In recent years, with affordable rents, Bushwick has become more attractive, and cafes, bars and galleries have opened.*****

Artists arrived, often partnering with local institutions. Photographer Daryl-Ann Saunders was one of twelve who set up studios in a local senior center. She had already begun a portrait series, Pioneers of Bushwick, and found that the pairing gave her an “in€ with the local residents.******

And Meisler, now an Adjunct Instructor at NYU, plans to go back in 2012 to “photograph the change, but more important, the character and special Americana that is also Bushwick-people living, laughing, enjoying and embracing the challenges of life.€

At some point on her journey she also learned that her predecessor, the teacher presumed dead, was alive and well and working nearby in Bushwick.

Meisler’s series Here I Am: Bushwick in the 1980s is on view at Soho Photo Gallery, 15 White Street, through December 31st.

- Catherine Kirkpatrick, Archives Director

Notes:

* Mahler, Jonathan, The Bronx in Burning, Picador, 2006, pages 206 – 213

** Mahler, Jonathan, The Bronx in Burning, Picador, 2006, page 224

*** Mahler, Jonathan, The Bronx in Burning, Picador, 2006, pagse 178-179

**** John A. Dereszewski, Bushwick Notes: From the 70′s To Today, and phone interview

***** T. Paul Cox, e-mail comments

******Daryl-Ann Saunders, e-mail comments

(Sorry-couldn’t get the superscript working in WordPress!)

The Fine Art of Personality

What Becomes a Legend…

Every neighborhood has one, a character so unique that they earn a place in local lore. The one I grew up with worked in the drugstore. Behind the counter he seemed so normal. He was polite to customers, had deep knowledge of his field. But taped to the front of the pharmacy counter were those pictures….

There he was, in a bathing suit by the river, flanked by reporters and police, his arms wrapped in chains-great massive chains, the kind used to secure elephants under the big top. Newspaper clippings attested this was a habit. Was it safe to buy medicine from him?

It was. He was kind, competent and caring. He helped older customers in the store and took an interest in people’s lives. But part of him liked to break loose and do Houdini-style magic with the media present. Back then, he was a legend in Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper. Today, he would have a website and hundreds of followers on Twitter.

There have always been colorful people in New York. Some take to the river, others to the streets, bringing with them a sense of joy, excitement and personal theater. But high rents and rough economic times have forced some to cut back. Many have relocated to friendlier environs or toned down (at least by their standards). Here are a few NYC legends seen through the eyes of several women photographers. A little hint: don’t be fooled by the clothes. If they have large imaginations, their hearts are even bigger. They’ve touched many people and inspired more than a few.

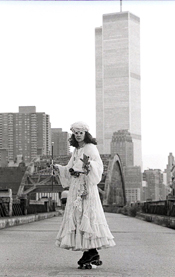

Rollerena

It doesn’t matter what his real name is, or if he really came from Gravelsnatch, Kentucky, though he swears there is such a place. For the person known as Rollerena, reality is a creative and highly flexible concept. Like a great actor carefully crafting a character for the stage, deep personal belief, consummate attention to detail, and appropriate costume outweigh all other considerations.

He’d always skated. That was a skill acquired early in life. But the persona had a slower, more careful and conscious evolution. Even his official name went through several iterations before it fit just right like an elegant glove.

The legend began to take shape in 1970. He didn’t care for the subways so decided to skate to work. The idea came to him not precisely in a dream, but when he was resting and spied his skates through a half open closet door. He practiced in Central Park and on the Upper East Side, and in 1971 appeared in the Gay Pride Parade as Rollin’ Skeets.

Then on September 16, 1972, he went into The Opulent Era, a shop that specialized in old Vaudeville clothes. “If you have a bathrobe with some glitter,” he said, “I’ll skate up and down Christopher Street.€ Everyone sprang into action. A gown was produced, then a straw hat and basket, and off he went. He skated into Dancing Danny’s, a bar at Christopher and Greenwich, and the place went wild.

A star was born. Requests for appearances followed. He would rest up after work, then head off with his outfit in a shopping bag. Sometimes he would change in the doorway of a co-op, startling the doorman. Then he “would be picked up at the Plaza Hotel in a limousine and driven to wherever I had to go.€ He was credited for starting the skating craze in New York, and was a favorite at Studio 54, where he always got in.

Rollerena’s wardrobe became ever more glamorous, and includes the Turtle Clutch, the Rose Fur Hat, (worn the night he danced with Nureyev at Studio 54), and the beloved Dingleberry Ring. A circus baton and bicycle horn are also favored items.

Though he no longer skates, Rollerena remains spectacular and has a busy social calendar. He enjoys meeting people and has inspired many. One was photographer Darleen Rubin who saw Rollerena flying down Christopher Street in the early 1970s. Pictures of their collaboration will be on display at the Jefferson Market Library September 7th through October 29th.

The Mayor of Grand Street

Photographer Meryl Meisler met Morris Katz in 1977 when he was out on the street greeting neighbors. He also put in appearances at the local police precinct and synagogue to keep people’s spirits up and to let them know he cared. He had to, it was his job. As the unofficial Mayor of Grand Street, he had responsibilities and duties to carry out.

If there a whiff of the carnival about him, one of his jobs during the Depression had been to guess people’s weights at Coney Island. He probably learned diplomacy there, and always had a ready supply of one liners (“I never lost my senses because I never had any”). Later he worked in the Garment District, but fashion didn’t seem to rub off: he freely mixed plaids with stripes, polka dots with zebras to create a distinctive personal style.

He might not have been fashionable, but he was always kind, handing out gifts and sweets to neighbors and children. He also shared a social worker with Auntie Mame, the real woman on whom the book and musical were based. Sometimes New York is a small town.

Mayor Katz passed away some time ago during a heat wave. He was in his 99th year.

A Haven for Artists

Born in France, Florent Morellet owned a bistro in the Meatpacking District that embraced all the vivid diversity New York has to offer: gay people, straight people, actors, artists, underground stars, movie stars, fashion designers, shady ladies of the evening and at lunch, local moms with children in tow. It was a place where creatives, really everyone, felt safe and could catch up on local news that was posted daily on the menu board. Pamela Greene discovered it while documenting the Meatpacking District, and always took an interest in whatever artistic project the staff or regulars brought out to share. If you went there, you became part of their friendly, creative tribe.

But Manhattan rents skyrocketed, and in 2008 Morellet was forced to close his restaurant. His concern lives on though his civic activism, and his creativity is channeled into his extraordinary imaginary maps.

Rich in plumage and visually arresting, these outsize personalities have inner strength and the courage to be themselves, even if it means standing or skating alone. They offer lessons in tolerance and friendship. They have many fans, and are fabulous inside and out. What’s not to love? Or take a picture of?

- Catherine Kirkpatrick, Archives Director