Tag Archives: Meryl Meisler

30 For 30: Friends Who Overcame and Inspired

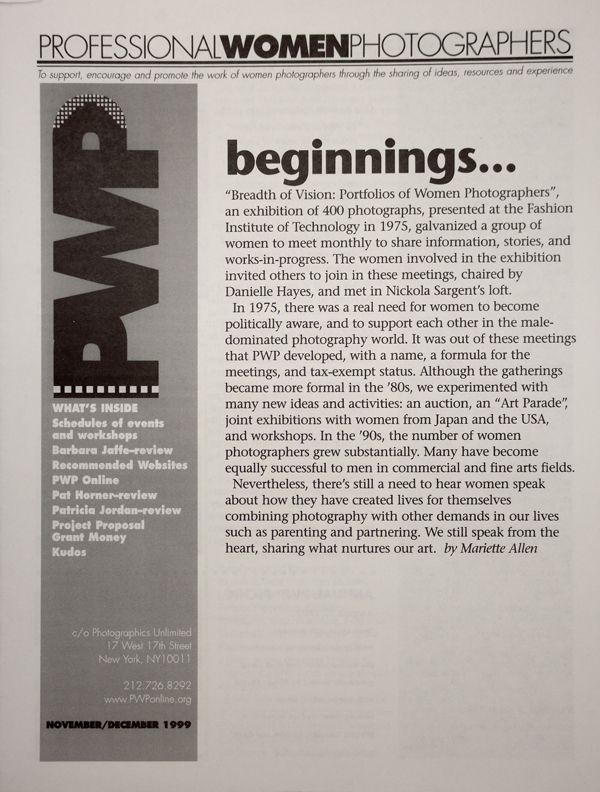

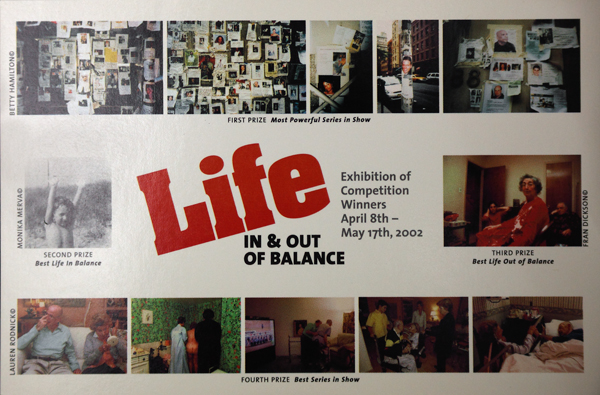

To celebrate Women’s History Month, we’re featuring items from the PWP Archives* each day on this blog. In looking back, we see not only where we started, but how far photography, women, and the world have come since 1975.

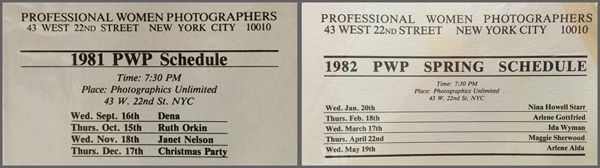

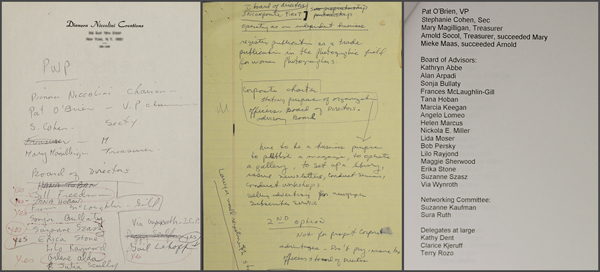

From the beginning PWP has had some very good friends. The guest speaker list from the 1981-82 season includes Ruth Orkin, Arlene Gottfried, Arlene Alda, and Maggie Sherwood of the Floating Foundation of Photography. Below are Dianora Niccolini’s notes for the first PWP board and outside advisors, along with a later list of people who served. It is impressive, and includes Kathryn Abbe, Sonja Bullaty, Frances McLaughlin-Gill, Lilo Raymond, Maggie Sherwood, Erika Stone and Via Wynroth.

Notes for the first PWP Board and outside advisors (left & center); list of people who served as advisors (right)

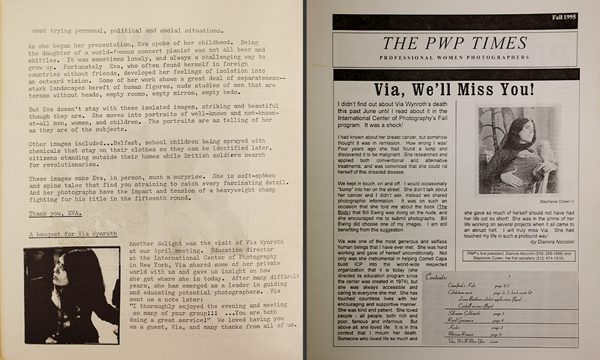

Via Wynroth was the first Director of Education at the International Center of Photography, and was extremely forward in her thinking and hiring practices. She had a huge impact on a generation of photographers, and supported organizations that supported them, including PWP. She was an early advisor, and a warmly received guest speaker who shared her work and thoughts about her life and career (PWP Newsletter below left). When she passed away far too soon from cancer, she was fondly remembered in the Fall 1995 issue of The PWP Times (below right). Her friends, including PWP members Dianora Niccolini and Meryl Meisler, still speak of her today; hers is a rich legacy that runs deep in many hearts.

Early PWP Newsletter featuring Via Wynroth’s talk (left); later article remembering Wynroth’s life (right)

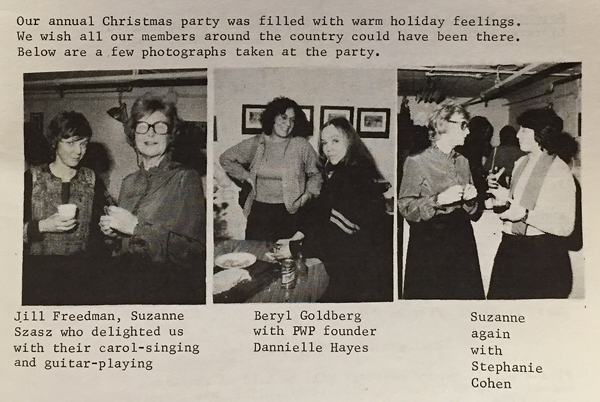

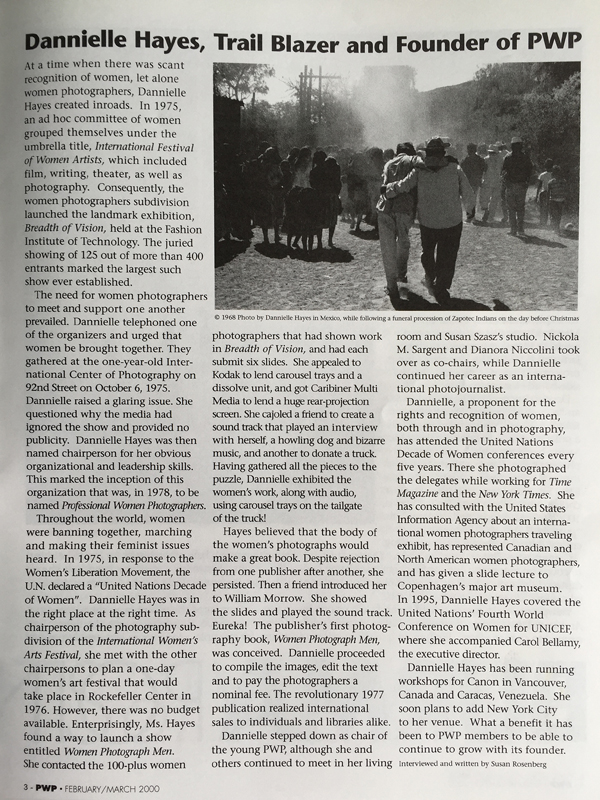

Danielle Hayes was the founder of PWP. Concerned the 1975 FIT exhibition Breadth of Vision: Portfolios of Women Photographers wasn’t getting enough attention, she called participants together for a bootstrap publicity campaign. It was from this group that PWP emerged.

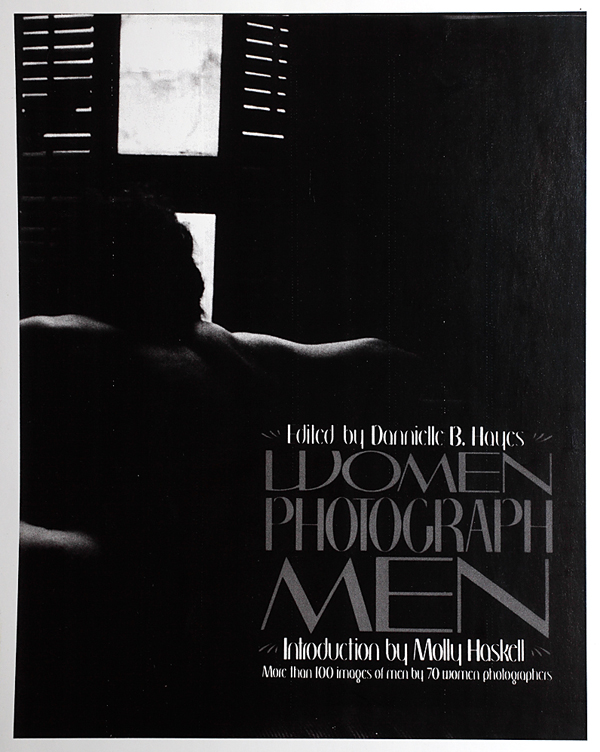

This was the lady who drove a truck into Rockefeller Center to get attention for her book concept, Women Photograph Men. She got that attention and more: a deal with William Morrow & Company. The 1977 book was historic, with 100 images of men by 70 women photographers, including Arlene Alda, Barbara Gluck, Joan Liftin, Mary Ellen Mark, Barbara Morgan, Martha Swope, and Suzanne Szasz. It also contained a half folio of color photographs, unusual for the time, and an introduction by renowned film critic Molly Haskell.

Not all the photographers who gathered at Hayes’ apartment for these first meetings were included in the book, so she graciously bowed out as leader of the “yet unnamed PWP.” She went on to a distinguished career as a freelance photographer, writer, illustrator, and designer. But a list of Hayes’ clients (which includes Time, Inc., The New York Times, and the National Geographic Society), or the places where she’s taught (Canon Creativity Workshops, Simon Fraser University, the New Jersey Institute of Technology), fails to indicate the wealth and richness of her ideas or the generous way she views the world.

Her outlook is truly global. She once approached J. Walter Thompson, trying to put Kodak and UNICEF together, and has worked in many countries, including South Africa, Niger, Uganda, Cameroun, Senegal, Ethiopia, Tunisia, Indonesia, Jamaica, Cuba, Peru,Venezuela, Argentina and Canada. Equally impressive is her affiliation with and work on behalf of a wide range of worthy causes, including CARE, UNICEF, the United Nations’ Women’s Conference, Helen Keller International, and the 2010 Winter Paralympic Games, for which she felt a special fondness.

A few years back Hayes suffered a massive stroke, but recovered. Currently she is on a cruise, but before she left, told friends not to email till she got back because she was too busy with other things. For Dannielle Hayes breadth of vision isn’t just the title of a show that came and went, it very simply is a way of life.

– Catherine Kirkpatrick

*The PWP Archives were acquired by the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, & Rare Book Library of Emory University

Links to all the 30 For 30 Women’s History Month blogs:

Help Me Please! Hopelessly Waiting…

Exhibition and Anger

Spreading the Word

Early Ads On Paper

Cards and Letters

A Lady, a Truck, a Singing Dog

Women of Vision

A Show of Their Own

Taking It To the Street

Sisters of Sister Cities

Sold!

Education and More

Face of a Changing City

Digital Enabling

Expanding Walls and Other Possibilities

A Wonderful Life–Lady Style

Branding–the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

The Great Change Sweeps In

PWP Goes Live!

Honoring the Upcoming

Continuity Through Change

Reaching Out

Eye a Woman Naked

Rapidly Multiplying Alternative Options

Women In the World, As Themselves

Kudos!

Friends Who Overcame and Inspired

Reversing the Gaze

Photography and More

Chicks Telling It Like It Is

Looking Back With Thanks

30 For 30: Taking It To The Street

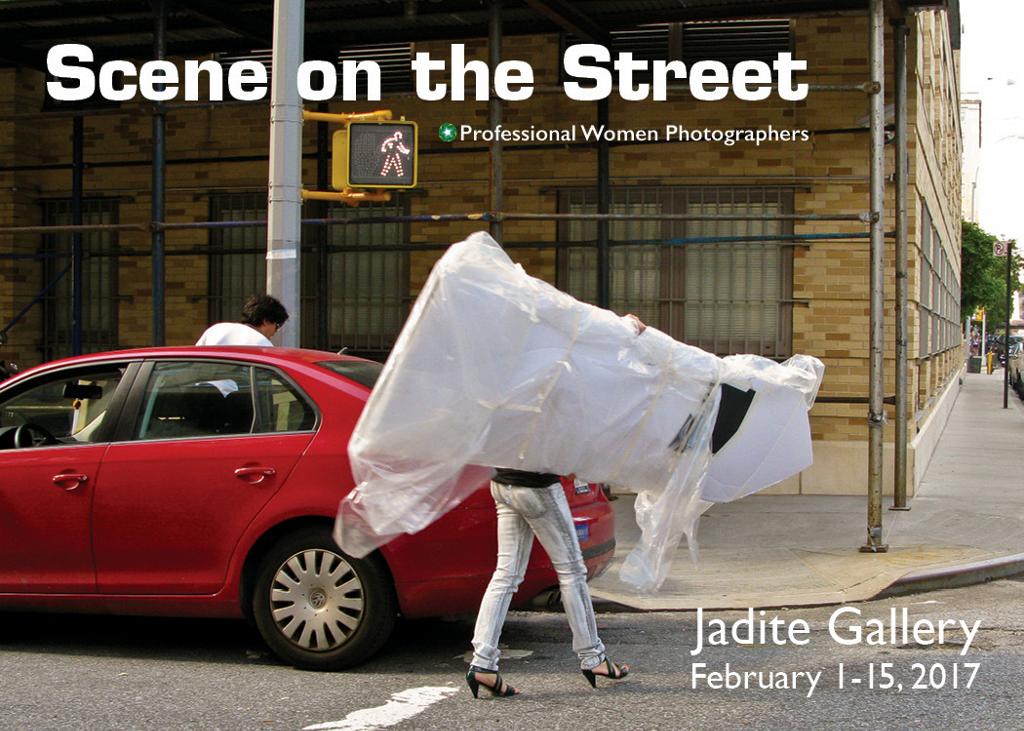

To celebrate Women’s History Month, we’re featuring items from the PWP Archives* each day on this blog. In looking back, we see not only where we started, but how far photography, women, and the world have come since 1975.

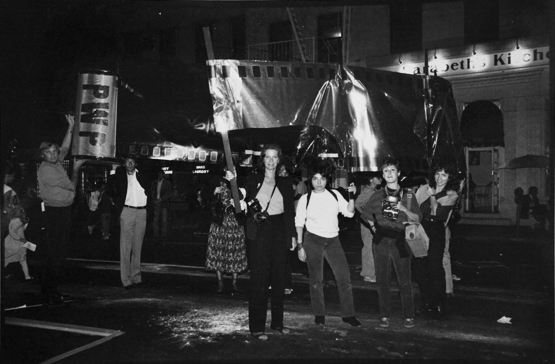

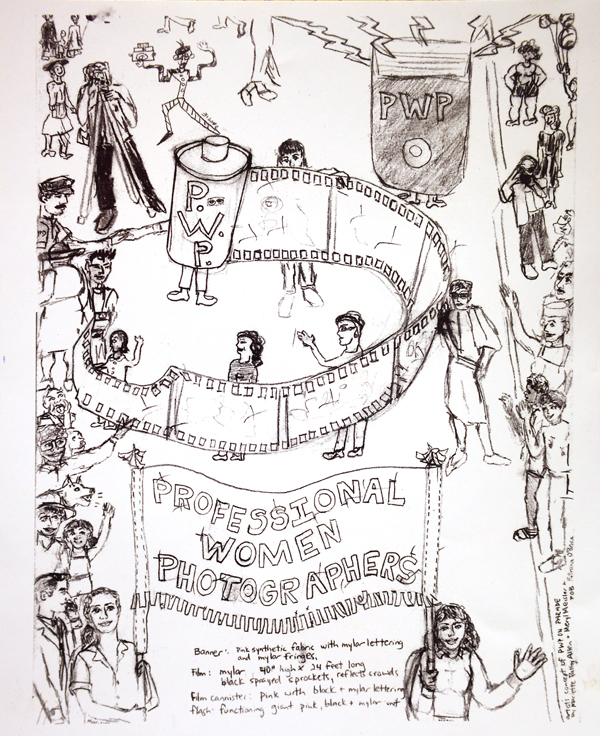

In 1983, PWP participated in an Art Parade that marched along upper Fifth Avenue, Manhattan’s “Museum Mile.” Meryl Meisler, Tequila Minsky, and Mariette Pathy Allen, president of PWP from 1984 to 1992, designed and executed a shimmering banner and promotional materials. Stephanie Cohen took these iconic shots of the march.

Meryl Meisler remembers: “I’d recently joined Professional Women Photographers, which remains my grownup “Girl Scout Troop” to this day. Mariette Pathy Allen didn’t have to ask me twice to help design the banners for the 5th Avenue Art Parade. Another PWP member, Teq Minsky, helped make the roll of film and we became fast friends and have remained so ever since. Patricia Jean O’Brien, Dave Channon, and Barbara Alper were among the marchers.”

– Catherine Kirkpatrick

*The PWP Archives were acquired by the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, & Rare Book Library of Emory University

Links to all the 30 For 30 Women’s History Month blogs:

Help Me Please! Hopelessly Waiting…

Exhibition and Anger

Spreading the Word

Early Ads On Paper

Cards and Letters

A Lady, a Truck, a Singing Dog

Women of Vision

A Show of Their Own

Taking It To the Street

Sisters of Sister Cities

Sold!

Education and More

Face of a Changing City

Digital Enabling

Expanding Walls and Other Possibilities

A Wonderful Life–Lady Style

Branding–the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

The Great Change Sweeps In

PWP Goes Live!

Honoring the Upcoming

Continuity Through Change

Reaching Out

Eye a Woman Naked

Rapidly Multiplying Alternative Options

Women In the World, As Themselves

Kudos!

Friends Who Overcame and Inspired

Reversing the Gaze

Photography and More

Chicks Telling It Like It Is

Looking Back With Thanks

Fire, Ashes, Fear: Bushwick in the 1980s by Meryl Meisler

By Catherine Kirkpatrick (PWP is reformatting its archival blogs, and decided to begin with this post on longtime member Meryl Meisler. Originally published in 2011 during her show at Soho Photo Gallery, is timely because an exhibition of her earliest work will open February 25, 2016 at the Steven Kasher Gallery in Chelsea.)

By Catherine Kirkpatrick (PWP is reformatting its archival blogs, and decided to begin with this post on longtime member Meryl Meisler. Originally published in 2011 during her show at Soho Photo Gallery, is timely because an exhibition of her earliest work will open February 25, 2016 at the Steven Kasher Gallery in Chelsea.)

It didn’t seem right. Why would a New York City teacher with benefits and a pension leave a full-time post right before Christmas? Everyone knew that Bushwick was a dangerous part of Brooklyn, and terrible thoughts and speculation began. Was the teacher even alive? Had she been…killed?

Thus began Meryl Meisler‘s artist statement for her 2011 Soho Photo Gallery show, but in 1981 it was a real concern. She’d had one camera stolen–not on the street, but in the classroom where she taught on the Lower East Side. But Bushwick, an area in north Brooklyn bordering on Bedford-Stuyvesant and Brownsville, was worse. Tourist guides left it out. No one wanted to go there. Meisler hesitated, but knew if she didn’t take the job, she’d slide to the bottom of the Department of Education’s list. She said yes.

In 1981 fear ran through the city. Dark days lay behind (the ’77 blackout, near bankruptcy, crime), and dark days lay ahead (more crime, AIDS, and crack cocaine). Every section was on edge, but some were worse than others. Bushwick was widely considered the worst. At least a few politicians ventured to the Bronx for photo ops (most famously Jimmy Carter in 1976), but no one went to Bushwick.

Its trip down had begun in the 1960s when working class families migrated to the suburbs, replaced by poorer families displaced by well-intentioned urban renewal projects elsewhere. As light industry and breweries vanished, so did jobs. There were Federal Housing Administration schemes, schemes by greedy landlords, and redlining by banks that stopped the flow of money to residents. Landlords torched buildings for insurance money and to oust tenants, and kids torched buildings because there was nothing else to do. Fire was a deadly, ever-present threat. The number of Welfare recipients rose, and by 1977, 80% of the population was unemployed. Infant mortality rates were the highest in the city, schools were overcrowded, drugs were rampant and dropout rates were high.*

Many of the problems were citywide. From 1973 to 1976, New York lost 340,000 jobs,** and in 1975 came close to bankruptcy. 1976 saw the worst crime stats ever, as well as the debut of New York’s infamous serial killer, Son of Sam. How bad could it get?

Worse. On July 13th 1977, Meryl Meisler and a friend were planning to boogy down at Studio 54 to the throbbing disco beat of Donna Summer and KC & the Sunshine Band. But any sunshine New York had was fading fast and it was about to get very, very dark. At 8:37 p.m., lightening struck power lines at a substation in Westchester, triggering a short.*** As Con Ed managers struggled and failed to readjust electrical loads, lights winked out all over the metropolitan area. As Meisler and her friend pedaled uptown, the night seemed to grow thicker. By the time they reached Studio 54 and found it closed, and a great darkness–vast, enveloping and complete–had settled like a shroud over the City of New York.

In the chaotic looting that began, Bushwick was the epicenter. In the main shopping district along Broadway (named after Manhattan’s famous avenue), stores were cleaned out and many set on fire. When the anger and darkness and burning were through, Bushwick, an area that had clung to its working class identity, lay in ruins.

For New York, the blackout represented rock bottom, the moment when all the terrible trends that had been gathering coalesced into one giant, awful photo op that the world, country and city could no longer deny or turn away from. Something–many things–had to be done.

By the time Meryl Meisler arrived in 1981, Bushwick had cooled down and settled into its role of urban ghost town. Photographic series exploring urban decay often feature great swaths of graffiti-covered brick, but in Bushwick, many walls simply weren’t there. The first thing that strikes you in her images from this time is the amount of rubble. It’s everywhere, all over the place–blocks and blocks of it–pierced by an occasional tottering facade or low cluster of houses that seem to lean against each other for support. There is a sense of eerie quiet, almost peace; you feel as if the images were taken in some distant war-scarred city, not a few miles from the financial center of the world.

By the time Meryl Meisler arrived in 1981, Bushwick had cooled down and settled into its role of urban ghost town. Photographic series exploring urban decay often feature great swaths of graffiti-covered brick, but in Bushwick, many walls simply weren’t there. The first thing that strikes you in her images from this time is the amount of rubble. It’s everywhere, all over the place–blocks and blocks of it–pierced by an occasional tottering facade or low cluster of houses that seem to lean against each other for support. There is a sense of eerie quiet, almost peace; you feel as if the images were taken in some distant war-scarred city, not a few miles from the financial center of the world.

Meisler took it in with an unflinching eye, coming to appreciate it’s strange beauty. There were ruins that rivaled anything from ancient Rome, a pure light unimpeded by tall buildings, magnificent backgrounds of clouds and sky. The surviving structures “whispered stories” and seemed to be “waiting for their portraits.” Meisler obliged. There were also street scenes reminiscent of small town life, filled with people who despite poverty, went about their lives and conveyed a sense of joy. That is what she focused on.

Using a low-cost point-and-shoot camera with cheap slide film, she began photographing on her way from the subway to the school, then back again on her way home. She was polite, always asking permission. When urban historian, Adam Schwartz, was planning a show on Bushwick in 2006, her name came up, and the little boxes of slides began to come out of the basement.

They weren’t in great shape. There were color shifts, nicks, and occasional green spots of mold. She began digitizing, then used Photoshop to color correct and clean up flaws. Which, she believes, didn’t change the reality. Initially she outsourced the printing, but now handles it herself. “I am a printer’s daughter,” she says, “no one could be as obsessive about them as yours truly.”

They weren’t in great shape. There were color shifts, nicks, and occasional green spots of mold. She began digitizing, then used Photoshop to color correct and clean up flaws. Which, she believes, didn’t change the reality. Initially she outsourced the printing, but now handles it herself. “I am a printer’s daughter,” she says, “no one could be as obsessive about them as yours truly.”

Looking at the magnificent output, it’s easy to forget Meisler had a day job, but she did, and took it very seriously. She has won many awards, including a Disney American Teacher Award, an Adobe Youth Voices Grant, a Chase Active Learning Grant, and a New York Foundation For The Arts Fellowship. She also started a photography program at I.S. 291, integrating “the children’s personal stories, health topics and…the history of the neighborhood.” Students’ work was exhibited in storefronts, parking lots, and projected onto building walls, in addition to being shown alongside the work of famous artists in galleries and museums.

Till the 1977 blackout, Bushwick wasn’t on anyone’s radar. The focus always seemed to be someplace else, generally the Bronx, which drew photo ops and the attention of presidential hopefuls like Jimmy Carter in 1976. But after the blackout, with a mayoral election looming, Bushwick came to the fore. Prodded by extensive New York Daily News coverage, democratic front runners Ed Koch and Mario Cuomo pledged to rebuild the decimated housing stock. According to John Dereszewski, then District Manager of the Bushwick Community Board, it was a huge challenge: ”I remember walking through the area and tripping over the ground and wondering ‘what the hell am I doing here?’ Was it hopeless?”

The answer is no, but its rebirth has been a long, tough slog, that isn’t over. Redevelopment started slowly, and the Koch administration began an immediate demolition program to clear abandoned buildings, which made the area safer and less demoralizing. Trees were planted, and through community involvement and pressure, the housing that was built was in keeping with the low-rise nature of the neighborhood.**** In recent years, with affordable rents, Bushwick has become very attractive to young people and creatives, and cafes, bars and galleries have opened.*****

And Meisler also learned that her predecessor, the teacher many presumed dead, was alive and well and working nearby in Bushwick.

Meisler has had several shows of her Bushwick work at the Living Gallery and Bizarre, which also published her two books (A Tale of Two Cities: Disco Era Bushwick, and Paradise & Purgatory SASSY ’70s Suburbia & The City). On February 25, an exhibition of Meisler’s earliest work of family and friends in her hometown of Massepeaqua and 1970′s nightlife will open at the Steven Kasher Gallery, 515 West 26th Street in Manhattan. It will run through April 9, 2016.

Meisler has had several shows of her Bushwick work at the Living Gallery and Bizarre, which also published her two books (A Tale of Two Cities: Disco Era Bushwick, and Paradise & Purgatory SASSY ’70s Suburbia & The City). On February 25, an exhibition of Meisler’s earliest work of family and friends in her hometown of Massepeaqua and 1970′s nightlife will open at the Steven Kasher Gallery, 515 West 26th Street in Manhattan. It will run through April 9, 2016.

Notes:

* Mahler, Jonathan, The Bronx in Burning, Picador, 2006, pages 206 – 213

** Mahler, Jonathan, The Bronx in Burning, Picador, 2006, page 224

*** Mahler, Jonathan, The Bronx in Burning, Picador, 2006, pagse 178-179

**** John A. Dereszewski, Bushwick Notes: From the 70′s To Today, and phone interview

***** T. Paul Cox, e-mail comments

(Sorry-couldn’t get the superscript working in WordPress! – Catherine Kirkpatrick)