Some Mother’s Son: The War Photography of Josephine Herrick

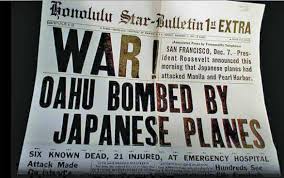

On December 6th, 1941, Pearl Harbor wasn’t a place on the mind of many Americans, if they knew about it at all. Located on the island of Oahu near Honolulu, it was home to thousands of servicemen and the U.S. Pacific fleet. Danger was thought to be elsewhere, in the war spreading across Europe. America, protected by sea and strong isolationist sentiment, wasn’t involved.

That changed the next morning when hundreds of Japanese planes dropped from the sky just before eight. Swooping down on the naval base, they bombed, torpedoed, and strafed till twenty U.S. vessels and hundreds of aircraft were crippled or destroyed. When they departed two hours later, the harbor was black with smoke, the water strewn with wreckage and crumpled ships. Nearly 2,500 servicemen perished, 1,177 of them entombed in the USS Arizona when a bomb struck the ammunition magazine. It was the day that changed the course of America, and sent the destinies of a generation spinning.

Unlike recent conflicts, Word War ll was a shared burden that cast a long shadow over many families. As troops headed overseas, people pitched in at home. Many women went to work in factories like Rosie the Riveter, and millions volunteered for the Red Cross, while others contributed in unique, personal ways. One of these was Josephine Herrick.

Unlike recent conflicts, Word War ll was a shared burden that cast a long shadow over many families. As troops headed overseas, people pitched in at home. Many women went to work in factories like Rosie the Riveter, and millions volunteered for the Red Cross, while others contributed in unique, personal ways. One of these was Josephine Herrick.

Herrick was born in 1897, the third child of a prominent Cleveland family. During World War l, she served as a Red Cross nurse in her home city, then attended Bryn Mawr, and later the Clarence H. White School of Photography in New York. There she mastered the technology and art of the discipline, exhibiting her work, winning several awards in shows at the Cleveland Museum of Art. In 1928, she opened a photo studio with her friend, Princess Miguel de Braganza, an American socialite who’d married a man of royal Portuguese descent. Located on East 63rd Street in Manhattan’s Silk Stocking District, the studio specialized in portraits of debutantes and children. Before Pearl Harbor, as conflict grew in Europe, Herrick joined the American Women’s Voluntary Services, training photographers to document news events and educate the public on blackouts.

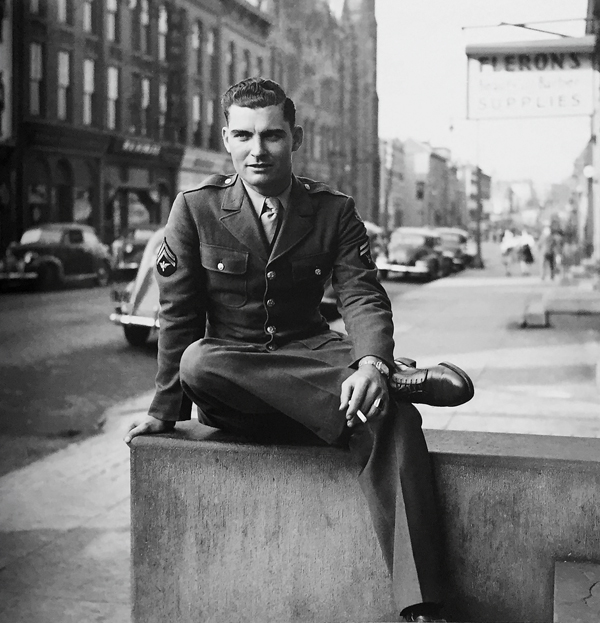

When America plunged into war, she mobilized thirty-five photographers to photograph servicemen heading overseas. A copy of the image along with a personal note was sent to each man’s family. It meant a lot because photography then was not the casual, ever-present thing it is now. It required a camera–out of reach for many in the Depression era–as well as knowledge of exposure, film stock, and printing. During those hard times, many families did not have pictures of sons heading off to fight, many of whom would not return.

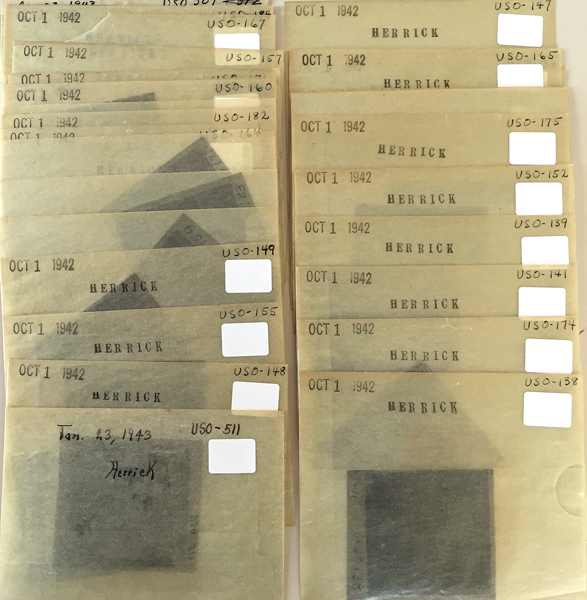

On a sunny June day, I had the chance to look at some of these negatives and images at the Josephine Herrick Project. Located in an old, nondescript building in lower Manhattan, the office has a view of the Brooklyn Bridge, but wouldn’t win any prizes for décor. But that’s not what it’s about. It is an organization dedicated to important, fundamental things–like creating images of sons so loved ones could hold onto them when they were gone.

Tucked neatly in glassine envelopes, the negatives fill several wood boxes. Collectively they are the portrait of a generation, individually the picture of some mother’s son. To hold them is to feel the pulse of history. You wonder how each man fared, if they were wounded, whether they made it home. You hope they did, though many did not.

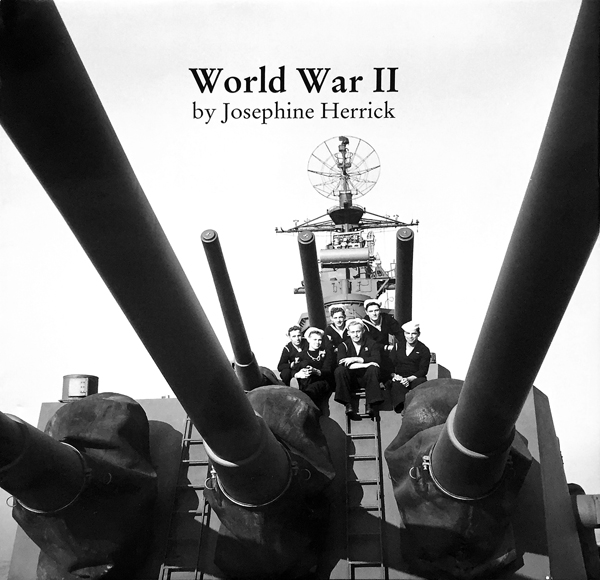

Also in their archives is a book of photographs Herrick took on a navy ship after the war. The setting is New York harbor on a day so sunny and bright it is easy to forget that the American Century was paid for with American lives. In the background the city rises, not yet too tall or threatening, preparing for its moment as the capital of the world.

The images are simple, but not simplistic, with a brightness that goes beyond the weather: the war was over, the troops were coming home, and for that day, maybe a little longer, equilibrium and happiness reigned. My own father served and survived, as did the father of Maureen McNeil, Executive Director of the Josephine Herrick Project. One day in the Pacific, she said, he drew kitchen duty on board his ship. He tried to get out of it, but couldn’t, and when the ship was attacked by kamikazes, it saved his life. Three thousand people died.

In the book I was delighted to find a picture of one of the men Herrick had photographed shipping out. He’d made it back, and sun in the pictures and outside in the street seemed a little bit brighter for it. For a moment the shadow of history had a soft edge.

After the war, Josephine Herrick went on to many other ventures, including a collaboration with Howard Rusk to photograph and teach photography to wounded veterans. Though she died in 1972, the organization she began continues her good work. Through dedicated volunteers and partnerships with local organizations, it brings the gift of photography to children, teens, adults, and seniors who otherwise would not be exposed to its healing powers and visual magic.

– Catherine Kirkpatrick

Beautifully told Catherine! What a treasure.

Betsy

It is amazing how many very talented women remain in the shadows.

Thank you for bringing Josephine Herrick to PWP’s attention.

Your portrait of her is so rich and tender, it is as if she were in the room with me. Beautifully done.