Zeke Berman: Thoughts and Pictures at an Exhibition

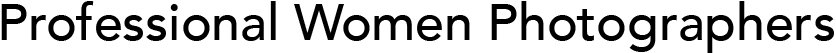

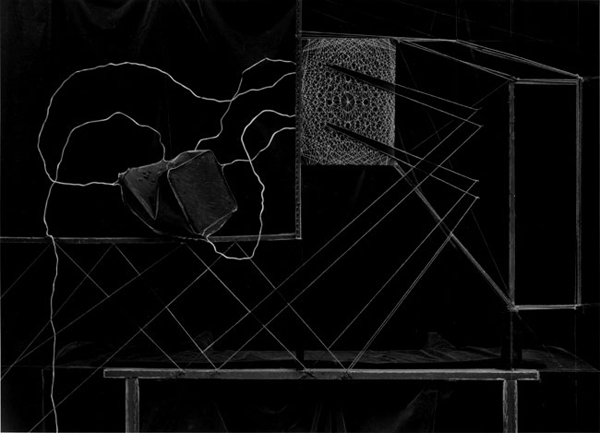

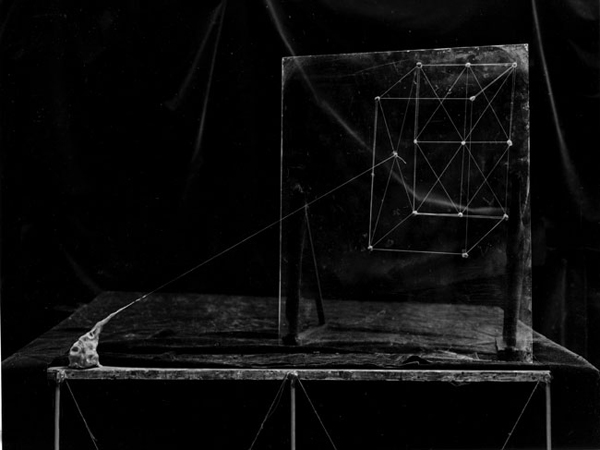

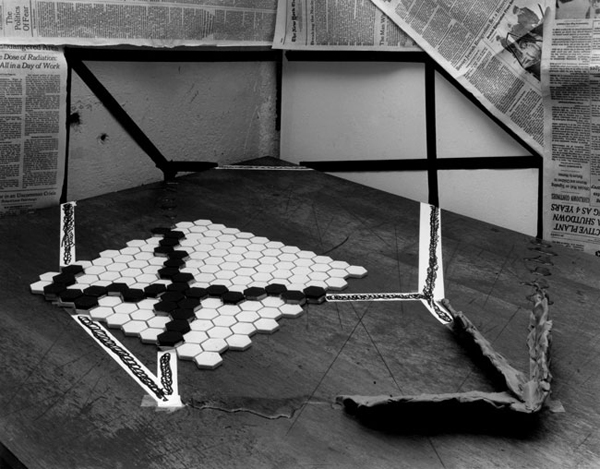

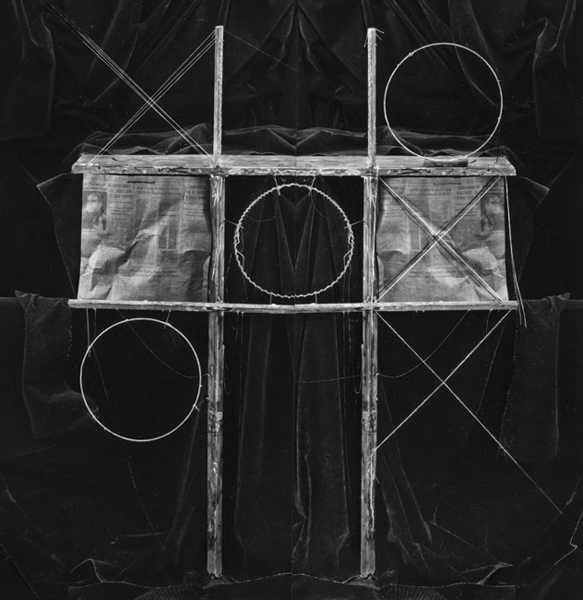

This is an odd one, but such is the power of pictures to take us unexpected places. On January 9th, I went to see Zeke Berman Still Life Images: 1980s at the Julie Saul Gallery. The photographs are large format, black-and-white; austere fields where light and form play out in imagined space. Slender lines of string and glue are balanced by heavier forms like drawing boards and mashed clay, with leaves and branches serving as occasional grace notes and reminders of the natural world. It is a strange beauty of common things, uncommonly arranged by an unusual mind. It raised questions of who, how, and why, but instead of looking up the artist, I went home and read Shakespeare.

Something in the images recalled the dark elegance and balance of Hamlet, a work about thinking and the importance of ideas. They also recalled the Olivier film, which unfolds in sparkling black-and-white, light strong and pure as reason itself, on sets that toy with perspective, drawing the eye ever deeper into imagined space.

How many photographs lead you to Shakespeare? How many take you anywhere at all?

Zeke Berman was born in 1951 and grew up in New York City’s West Village. His interest in sculpture began at eleven with a woodcarving class at camp, and continued at the High School of Art & Design, where he studied other mediums, including printmaking and drawing. His family was supportive, and through his father who collected antique microscopes (and worked for a firm that imported Zeiss instruments), he developed an interest in optics and visual perception.

The late 1960s and early 70s was an exciting but turbulent time to come of age. America was involved in Vietnam, and many social and cultural mores were under attack. Change was in the air, and at the Philadelphia College of Art (now the University of the Arts), Berman found a sculpture department split between traditional figurative study and a new approach that favored unusual materials used in unexpected ways.

In Philly, he also chanced upon the oscillating window illusion at the Franklin Institute. This display illustrates a quirk of visual perception where an object spinning one way seems to reverse and spin the other. For Berman, this was an “aha” moment. If the human mind could misperceive something so fundamental, it had to be, he said, “an interesting and very deep rule.” He took note, and began to read about perception, including serious texts like Kurt Koffka’s Principles of Gestalt Psychology.

Berman spent his junior year in Florence, drinking in Renaissance and contemporary art. Impacted by Donatello and studies of linear perspective, he also followed Conceptual and Minimalist trends at the Centro bookstore. There he discovered the work of Carl Andre, Lucas Samaras, and Jan Dibbits whose Perspective Corrections made a deep impression. Photographing squares of tape and rope laid on fields and floors, Dibbits explored notions of nature and design, distortion and illusion. Berman filed these away, not sure what direction his life and art would take.

In Italy, he borrowed his roommate’s Pentax to snap scenes and document wax models before they were melted down. With images replacing the objects they were meant to record, subtle issues, still subliminal, of primacy and permanency were raised.

Berman remembers his college work as unremarkable except for one project where he painted a gallery black and hung string from points around the room. This immersed the viewer in an alternative, wholly constructed world, and sparked his interest in string against a dark background, motifs that would reappear.

Returning home, Berman did a “little bit of casting, a little bit of welding,” moving generally in an abstract direction. He skipped grad school, living with his parents for a while before moving into a loft on Eldridge Street. It was different time, long before the great real estate boom swept though New York like a scythe. The city was more dangerous, but offered unique opportunities to those starting out. Artists and galleries could afford to rent downtown, and many landlords had space they didn’t know what to do with. Berman moved in, “homesteaded” the loft, and stayed for the next twenty-five years without a lease.

To support himself, he learned photo retouching, and found work at a high-end studio where he also learned paste-up and mechanicals. More reading on science “turbocharged” his developing sensibility, and formal classes built a strong foundation in darkroom and black-and-white. In the studio there was pressure to create, but out taking pictures, a sense of freedom and joy. It was inevitable the two worlds would meet, and in 1975-6 they did.

One day Berman put tape and string on the floor, looked through the viewfinder, and had an epiphany. All the ideas about optics, perception and art came together, he said, and “found form in the studio.” While the images contained elements of drawing and sculpture, these could not stand alone, but worked only in the context of the photographic frame.

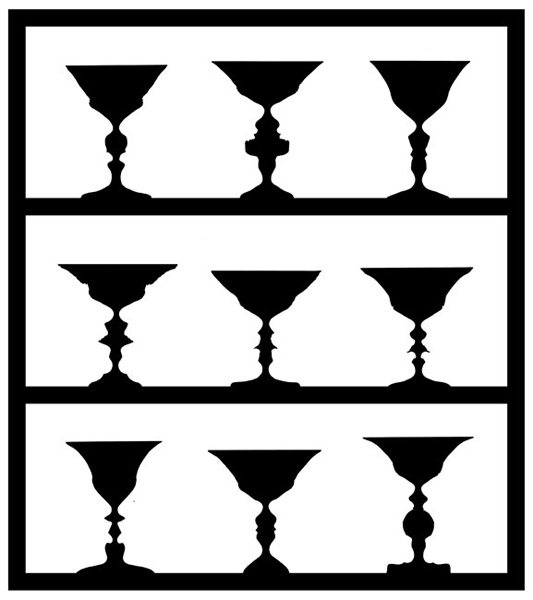

The gift of a view camera forced Berman to work more deliberately and deal with an inverted image, which sparked thoughts about optics and perception. In Goblet Portraits, he explored foreground/background dominance and riffed on Fox Talbot’s Articles of China. In another experiment, he drew a Necker cube on the ground glass then projected it with light through the back of the camera to a set where he refined it with tape and pins. He flipped and seamed negatives, erased spacial clues with black velvet. As humans, he said, “we are always completing things.” When we can’t, we are forced to think and see new ways.

For Berman, all studio work is a journey, the “result of coming to understand something.” Certainty is dull, the quest profound. Anchored in photography, his images allude to the wider field of art, engaging the mind and eye with playfulness and rigor. An alternate world, it is real and compelling as any natural scene by Wynn Bullock or Paul Strand, connected to the classic tradition by the use of large format, draped studio, and spectacular prints.

At some point, Berman felt the string and black velvet were “getting too abstract,” and began to photograph clothing. One day he froze a shirt to use as a prop, and found it so interesting he started to freeze other things. He began to notice the ice, and when it didn’t work in black-and-white, switched to color. He experimented with sugar and plastic as mediums–a sculptural thing–before settling on gelatin, which he buys in fifty pound bags from pharmaceutical supply houses.

Along the way there have been awards, including a Guggenheim fellowship and NEA grants, exhibitions at galleries and museums, but when we spoke, these were not mentioned. For Berman it was about process and search: the life of the mind in a studio setting, reaching for ideas and trying to work them out.

Zeke Berman Still Life Photographs: 1980s runs through February 20th at the Julie Saul Gallery. It is magnificent, go see it.

– Catherine Kirkpatrick

hi, Katherine

this is an excellent piece! so interesting. Thanks for sharing.

Diane Drescher