Ruth Gruber: Words, Pictures and History

From humble beginnings in Brooklyn, Ruth Gruber rose by her own talent and determination to become a writer, photographer, and humanitarian of the world. At twenty, she was the youngest Ph.D.; at age one hundred, with the exhibition Photographs as Witness, 1944-47 at Soho Photo Gallery, she is still going strong.

Gruber was born in 1911, the fourth of five children, to David and Gussie Gruber, Russian Jewish immigrants who settled in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. She flourished academically, and by fifteen was attending NYU where she fell in love with German culture.

Eager to escape the “shetl called Williamsburg,” Gruber accepted a fellowship in 1930 from the Institute of International Education for postgraduate study at the University of Cologne. There she wrote about the work of Virginia Woolf (“my Bible”), and a year later received her Ph.D. magna cum lauda. She also witnessed the rise of Nazism and the persecution of Jewish citizens. With the instincts of a journalist, she read Mein Kampf and attended a Hitler rally, telling herself: “I have to see what this man is like. I have to understand.” The German family she boarded with was horrified.

Returning to America, Gruber found herself a celebrity, but was unable to find work. The Depression was on, and “jobs went to young men, not young women.” Then one of her articles about the colorful ethnic neighborhoods of Brooklyn was published by the New York Times, and soon she was writing for the New York Herald Tribune. In the 1930′s, as the first foreign correspondent allowed to fly into Siberia, she documented Gulag prisoners, pioneers, and women living under Fascism.

In 1941, Gruber was named a special assistant to Secretary of the Interior, Harold Ickes, and sent to Alaska, then a territory, to study it as a possible location for homesteaders and returning veterans. She covered it by dogsled, truck and plane, photographing extensively with Kodachrome film. It was there, in extreme weather conditions, amid the peaceful Eskimos, that the girl from Brooklyn developed the ability to “live inside of time,” a special patience that would serve her well as conflict enveloped the world.

Throughout Hitler’s rise to power, the U.S. Congress had refused to lift the quota on Jewish refugees, but in 1944, Franklin Roosevelt allowed a thousand from Italy to visit the United States as his “guests.” Gruber was assigned to escort them, many still in their concentration camp uniforms, across the Atlantic on the Henry Gibbins, a ship hunted by the Nazis. Fearing Gruber would be killed if captured, she was made an honorary general to ensure her protection under the Geneva Convention.

On board, she quickly developed a rapport with the refugees, and sought to take down their stories. The men demurred. “It was too obscene, and you’re a young woman,” they said. But she replied: “Forget, if you can, that I’m a woman…. You are the first witnesses coming to America. Through you, America will earn the truth of Hitler’s crimes.” Everyone began to talk.

The refugees were held at Fort Ontario in Oswego, New York, behind barbed wire. As the government debated their fate, Gruber lobbied to keep them in the country through the end of the war. In December 1945, President Truman announced they could stay. It was the only effort by the United States to shelter Jewish refugees during World War II. These extraordinary immigrants included Dr. Alex Margulies, who became a distinguished radiologist and contributed to Cat scan and MRI technology; Rolf Manfred, instrumental in developing the Minuteman missile and Polaris submarine; Leon Levitch who became a composer; and Dr. David Hendell who became a dentist and pioneered the bonding of teeth.

In 1946, covering the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry on Palestine for the New York Post, Gruber visited the Displaced Persons’ (“DP”) camps in Europe and the Middle East. The Committee unanimously recommended that the British, who administered Palestine, allow 100,000 DPs to settle there, but their foreign minister, Ernest Bevin, rejected the finding.

The United Nations then appointed a Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP), which visited refugee camps, accompanied by Gruber for the New York Herald Tribune. On July 18, 1947, listening to testimony at the Jerusalem YMCA, she learned a ship called the Exodus 1947, bringing 4,500 Jewish Holocaust survivors to Israel, had been attacked by British destroyers. Gruber took leave of UNSCOP and went to Haifa to cover the story.

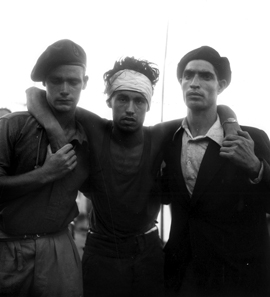

There she found the Exodus, built to hold a few hundred, with a gaping hole in its side, a crumpled deck and lifeboats dangling at odd angles. Unarmed, it had been attacked from two sides by British warships. Among the casualties were two orphans shot dead for throwing an orange and a can of beef at boarding marines.

The wounded, removed first, were stripped of their bandages to make sure they were not feigning injury to stay in Palestine. The rest of the refugees were segregated by sex, sprayed with DDT, and forced, without regard for family units, onto three questionable “hospital” ships that would take them to Cyprus prison camps. Gruber photographed the scene, “more with my heart than with my fingers,” then flew to Cyprus to meet the arriving ships.

They never came. Nobody seemed to know where they were; it was as if they had simply vanished. Waiting for news, Gruber photographed the prison camps in Cyprus, “a hot hellhole of desert sand and wind, of tents and Quonset huts with a long road hemmed in by two walls of barbed-wire fences and a wooden watchtower guarding the whole camp. The architecture had come straight out of Auschwitz.” There was no water, privacy, or sanitation. “You had to smell Cyprus to believe it,” she wrote. Yet approximately 52,000 Holocaust survivors were imprisoned there in the years following the war.

Finally Britain directed the three hospital ships to Port-de-Bouc, France, where the Exodus had started out, and Gruber hurried there. But the prisoners refused to debark, and eighteen days later, Britain decided to send them back to Germany, outraging the world. Of three journalists allowed onto the ships, Gruber alone was permitted to photograph. Boarding the Runnymede Park, a vessel named for the site where the Magna Carta was signed in 1215, she took the famous picture of refugees raising a swastika-painted Union Jack. Having endured German concentration camps, the survivors were enraged to find themselves imprisoned again by the liberators.

Gruber quickly developed a rapport with them. Many gave her the phone numbers of relatives, begging her to let them know they were alive. They encouraged her to take pictures and she did. Asked by the British to surrender her film, she refused. The Tribune shared the images with the Associated Press, telling Gruber “they don’t belong to the Herald Tribune, they don’t belong to you, they belong to the world.” Many of these images, which brought sympathy for and attention to the DPs, are in the current exhibition at Soho Photo Gallery.

Gruber’s relationship with the truth is simple and direct: just tell it. Nor has she ever worried whether she was or was not being objective, saying “you have to understand the feeling of the person you’re interviewing…to be compassionate…to understand what the person is going through.”

By photographing the Dps not as “a people,” foreign and dispossessed, but simply as individuals trying to recover a semblance of ordinary life, Gruber captured a deeper humanity. There are pictures of a father putting together a makeshift bassinet for his son, elders improvising an outdoor classroom for children, mothers proudly holding their babies.

In words that accompany the images, Gruber captured their fierce will to survive and have their children survive. “It was the babies who gave meaning to the whole Exodus,” she wrote. “It was for them the parents had endured the ordeal of DP camps and the travel in leaky boats.”

As one mother told her, “I am going to live for this baby so that my child won’t be killed in a gas chamber…. I am going to live so that my child can grow up in decency without being afraid.”

In a recent Q & A session at the Congregation Shearith Israel, Gruber said, “the more I wrote, the better my pictures grew. The more I took pictures, the better my writing grew.” And that is the strength of this show, its wonderful blend of images and words. The images give us the immediate visceral sense of the scene; the words fill in the historical context.

It is important to remember that if Ruth Gruber had not captured these images and accounts, details of this moment of history-the human part-would have slipped by. The general outline would have been known, but the sad eyes of men and women who had seen too much, the somber yet hopeful faces of their children, the blood and broken limbs of the wounded-would have been lost. She also recognized that her own life’s work was tied to the rescue and survival of the Jewish people, and went on to write many stories and books about it.

There is something about Ruth Gruber-her quiet persistence and personal grace, her sympathy for the individual coupled with her understanding of the larger historical sweep-that is compelling and unique. This is special show by a special lady, a single person who made a very big difference. Go and be inspired.

Ruth Gruber is scheduled to appear at Soho Photo Gallery on Thursday, May 24 at 6:30 pm for a screening of Ahead of Time, the Oscar-winning documentary about her life. She will also sign her book, Witness.

- Catherine Kirkpatrick, Archives Director

Quotes were drawn from:

Ruth Gruber’s May 9, 2012 talk at Congregation Shearith Israel in Manhattan

Ruth Gruber’s book Witness: One of the Great Correspondents of the Twentieth Century Tells Her Story, Schocken Books, New York, 2007

Wall text accompanying the images of Photographs as Witness, 1944-47 at Soho Photo Gallery

I love reading a post that can make men and women think.

Also, thank you for allowing me to comment!