Sgt. Pepper Uncovered

This post was named to Photoshelter’s list of Best Blog Posts of 2011.

She’s always dressed like a babe: white trench coat with no sign of anything underneath, a clinging jumpsuit, a sparkly blouse that reveals far more than it covers. Then again, it was TV and ratings were involved.

When Angie Dickinson starred from 1974 to 1978 as Sgt. Leanne “Pepper” Anderson in NBC’s Police Woman, it was groundbreaking television. Those were the years women were pouring into the work force, and entering professions like law enforcement and photography that traditionally had been the provence of men.

But television always plays catch up to social trends, and glamorizes them with little regard for the truth. In the case of women entering the police, the reality was far tougher and more prosaic than TV land ever let on. Certainly their clothes, especially when going undercover, weren’t anything like Sgt. Pepper’s. But one photographer took a closer look at the real thing.

Jane Hoffer is one of those quiet PWP members who astounds you with her accomplishments. She has an MA and Ed.D from Columbia University’s Teachers College, and was working on her doctorate when she took an elective in photography that changed her life. While eventually she finished her dissertation (on the “Technical and Aesthetic Developments of the Photo-Essay”), she began taking photography courses at the New School, SVA and ICP, and in the mid 80′s went into the field full time.

Hoffer has photographed Paul Newman, Thomas Friedman of The New York Times, and traveled with the Boys Choir of Harlem. While there’ve always been commercial projects to pay the rent, there’ve been others that were labors of love. “I used photography to put myself in places I couldn’t go without the camera,€ she says. And in the early 70′s she found herself riding with the police-an unlikely gig for a quiet artist who is also a practicing Buddhist.

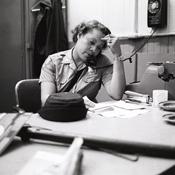

Hoffer began the project in the 70′s when she belonged to a group called Women Photographers of New York (founded by PWP’s first president, Dianora Niccolini). Members would suggest topics for exploration and possible exhibition, and one topic was women at work. At the time, Hoffer was teaching photography at John Jay College of Criminal Justice where she knew a woman who was a Buddhist…who said she could contact a policewoman friend of hers who was also a Buddhist…who would be willing to let Hoffer ride with her and be photographed. Official permission was granted and the project got underway.

“In the early 1970′s police women were put on patrol. I was a young photographer and was fascinated by the emerging roles of women in police work,” Hoffer says. “I photographed them in their precinct houses, their patrol cars and at the firing range. I photographed officers, sergeants, auxiliaries, physical education instructors at the academy and emergency service women.€

While photography has traditionally been predominately male, there have always been great women photographers. Julia Margaret Cameron, Dorothea Lange and Margaret Bourke-White are a few who come to mind. But women in law enforcement had a tough time just getting in. While they’ve been a part of the NYPD since 1845, for many years they were limited to the role of “matron,€ with duties that included searching and guarding female prisoners, and working with youths. It wasn’t until 1973 that they were known as “Police Officers€ and were assigned to regular patrol duties due to the 1972 amendment to Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that prohibited state and local agencies from gender-based job discrimination.

Even then, according to Kathy Burke, retired NYPD Detective 1st Grade and Past President of the International Association of Women Police, they were treated differently in large ways and small. For instance, while men had a 4 inch 6 shot revolver, women had a 3 inch 5 shot revolver. During target practice, each police officer had to get off 6 shots in a set period of time. Men could just fire their six shots, but women were forced to stop after 5 and reload, a somewhat tricky procedure, and still finish in the allotted time. The new women officers faced hostility from men in the department, and also from other women. Police wives protested when their husbands were paired with female officers. They feared amorous entanglements would ensue or that their husbands wouldn’t be as safe as they would be with a man. And women who had been part of the force in more traditional capacities resented the newcomers and the changing requirements of the job.

The job, says Detective Burke, is “filed with good times…filled with sad times. When the times are hard, they’re really really hard.€

In working on the project, Hoffer says she “learned a lot about myself and how I work with people. I eventually became an event photographer and it was probably these early years, working with women on the force, that helped me develop my “people skills.” I know when to charm and when to be invisible.€ She also brought her own peaceful karma to the project that began at the 13th Precinct on Manhattan’s East Side. Hoffer wanted to catch some action, but since police officers are not allowed to draw their weapons without justification, posing and set-ups were out of the question. So she went up to the 41 in the South Bronx (aka Fort Apache) on the night of a full moon…and nothing happened! That evening there were no incidents or events, just some very bored police officers who complained that Hoffer was a jinx.

But the danger is very real. While one of the women Hoffer photographed never drew her gun once in her entire career, Detective Burke was shot, and other women have died in the line of duty. The only thing that doesn’t quite live up to the dramatized versions is the outfit. But then it’s about much more than glamor. According to Hoffer, one of these early officers said “they faced more prejudice from fellow male officers than they did from men on the street. Because men on the street recognized and respected the uniform.€

I live near the Police Academy, and last week saw a female police cadet on the 23rd Street subway platform. Her face didn’t give out much and I thought about the isolation the earlier women officers suffered when they were 1% of the force. Then the cadet was joined by three other female cadets and a man who seemed to be an instructor at the Academy. They laughed and chatted. As people crowded onto the train, only one cadet managed to grab onto a pole. So the other cadets hung onto her and joked about bonding and being a family. They seemed comfortable with themselves and with each other.

Several times I thought about reaching out, asking them what it was like to be a female recruit in 2011. But every time I felt the urge to speak, I was reminded of the distance between us, between civilians and the police. The dark blue shirt and pants and jacket might not be as chic as Sgt. Anderson’s outfits, but it was The Uniform, and as such, commanded respect. No matter which sex was wearing it.

Police Commissioner Ray Kelly said that “the history of women in law enforcement dates back more than 100 years, but the most significant progress has been packed into the last few decades….Women are continuing to make history here, and have a powerful influence on the well-being of New Yorkers.€ The world moves forward, if slowly.

Jane Hoffer’s pictures will be on exhibit at the Police Museum in Lower Manhattan from February 8th through May 9th.

One of her prints, “An Officer at the Firing Range,” is in the PWP Archives.

- Catherine Kirkpatrick, Archives Director