A Desk(top) of Our Own

A Desk(top) of Our Own

It was different then. Every time I look at early material from the PWP archives, I’m struck by the overwhelming evidence of a different time and a very different way of doing things. It wasn’t so long ago-the group was founded in 1975 and got going in the 80′s-yet everything seems so utterly different.

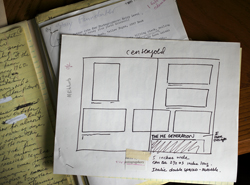

The first thing you notice is paper. Lots of paper, nothing but paper in the earliest folders-reams and reams of it! There are no electronic files-no Word docs, psds, pdfs, CDs, DVDs, e-mail, html, and most of all, no reference to urls. There were no blogs, no instant publishing. Only paper, ideas, and need. If you wanted to communicate back then and get the word out, you had to engage in manual labor-writing by hand on a piece of paper, typing on a typewriter, cutting and pasting using real scissors and actual paste. If you made a mistake, you helped yourself to some Wite Out (or as correction fluid was known in one of its earliest forms, “Mistake Out€).

You had to create copy, write or type that copy up, gather real photographs on resin-coated or gelatin silver paper for announcement cards, publicity and publications. The desktop you worked on was actual, not virtual, probably Formica or wood.

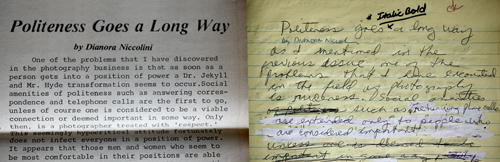

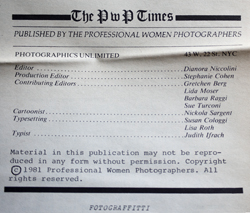

Before the current Imprints Magazine and the Professional Women Photographers Magazine that ran from 2005 to 2008, there was the very first PWP publication, The PWP Times that ran from 1981 to 1984. “We were working to establish PWP as a viable…respectable organization,€ recalls Dianora Niccolini, the first president of PWP and editor of The PWP Times. “We wrote about things that were happening and should be of interest to women photographers.€ There was a hunger and a need because up till then, she said, there had been “an unwritten rule that no one hired a women for photographic work.€ But the times were changing and new voices were demanding to be heard.

Small publications have always held a place of honor and influence in the literary and visual arts. A couple of examples that come to mind are The Yellow Book (1894 to 1897) that epitomized the Aesthetic Movement in Britain, and The Dial (in its first incarnation from 1840 to 1844) that promulgated the ideas of the American Transcendentalists. These small publications seem to last on average about four years, as if the sudden burst of energy and new ideas required to sync with, then sway the zeitgeist, exhausts their publishers, causing them to fall by the way. These publications are usually closely associated with a specific artistic or social movement; in the case of The PWP Times with the flowering of feminism and the emergence of the feminist press, as well as the entry of women into photography and the arts in general.

These publications require a special measure of energy and devotion, and are usually run by strong, individualistic people with a unique vision they’re determined to convey. Sometimes too, these leaders verge on the dictatorial, though generally in a benevolent and productive sort of way. As Ms. Niccolini said of creating The PWP Times, “a couple of women [members] wanted to vote on it, but I said ‘no, we’re going to do it, period.’€ And they did.

“It was an act of love,€ said Stephanie Cohen, who as production editor stayed up many nights putting the publication together. “Dianora and I did it all.€ On a very big, very real desktop of their own.

Each issue was devoted to a prominent woman photographer. In some cases, like Barbara Morgan and Lisette Model, they were well along in years. “I wanted to highlight and honor women photographers who…really opened the door, paved the way,€ Ms. Niccolini recalled. “Honor your history; you learn from it.€

Message received, lesson learned. I am currently in the process of digitizing issues of The PWP Times so they can be read on a virtual desktop as well as an actual desktop.

Catherine Kirkpatrick, Archives Director